Jones’ last patrol was on the second [July 1918]. Logbook entry:

Engaged 8 Pfalz scouts who went down. I got one in flames and two others were crashed. Then when formation was a bit scattered ten Fokker Biplanes came out of the sun and shot down Davidson in flames and McCreery. Jones was looking in front and a Fokker got us from 20 yards behind. Killed him and got us practically out of control. Landed at St. Marie Capelle. Crashed. Richthofen Squadron and 7th Pursuit Flight.

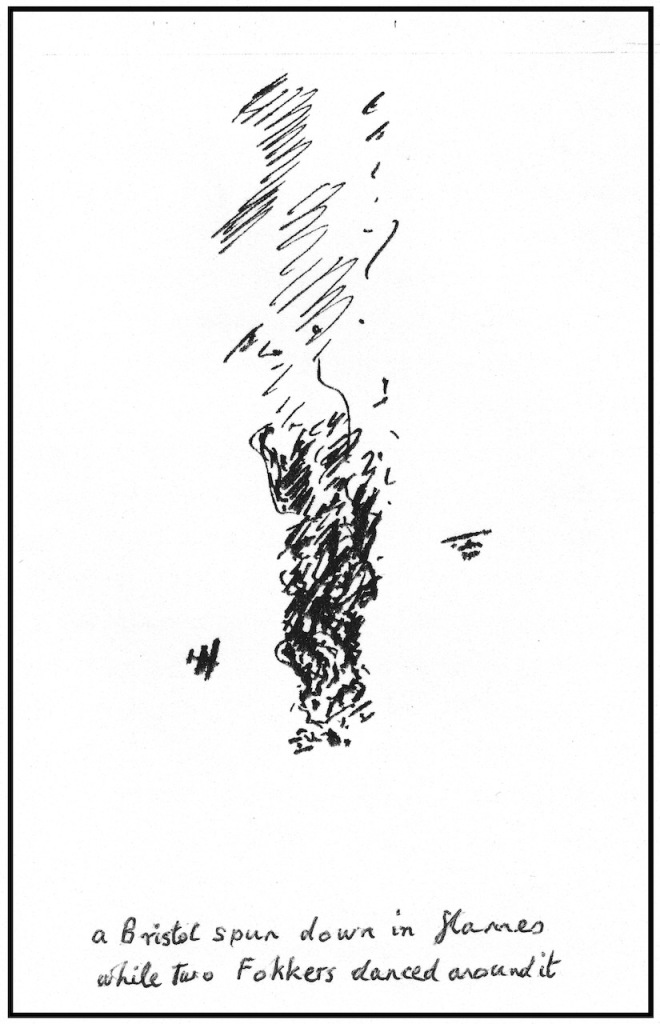

The Hun I got was on a Bristol’s tail and did not see me coming. Jones thought he got one too. Then the other Fokkers came in from astern and suddenly the sky was full of tracer. A Bristol wrapped in flames spun slowly down ahead of us while two Fokkers danced a jig around it.

Jones1 leaned over my shoulder for a moment and then everything happened at once. Jones tapped me on the top of the head, our ‘extreme emergency’ signal, and I kicked on full left rudder, stick hard forward to the left, and ducked: there was a very brief stuttering burst from a Fokker’s twin guns, I felt a blow on my left elbow as if I had been hit by a hammer, the aileron controls went out of action, one of the landing wire flew free and thrashed the fabric of the bottom plane, and a bullet went through my windscreen six inches in front of where my nose had been a moment before: then, as suddenly as it had happened, it was over. I expect another Bristol made a pass at the Fokker who had me cold: only able, without ailerons, to fly straight and fairly level. Having found that the aeroplane would fly, and pointed her for the lines, I looked round to see Jones sitting quietly on his little seat, his head resting on the butt of his gun. When I put my hand on his shoulder, I knew he was dead. I decided to land at St. Marie Capelle, the first field I came to, though I felt sure that nothing could be done for him. One of the undercarriage struts had been shot through and collapsed when we touched down, but we crunched to a stop without turning over and I shouted to some men for an ambulance. A stretched party came quickly and Jones was lifted from his cockpit, but there was nothing to be done: he had died instantly.

After Jones had been carried away, Johnstone2 came over for me in a Bristol and took me back to Boisdingham, where I made my report. I reported that Jones had claimed a Hun in the first part of the dogfight when he had leaned over me and shouted that he had got one and seen it crash. I do not think that he could have seen it crash, but I know that he must have felt sure that he did. We were about 15,000’, and he could not have concentrated on it in the middle of a fight for long enough to see it reach the ground, nor could he have seen it from that height. When fighting at our usual operational heights, unless a Hun went down in flames or broke up in the air, almost the only chance of getting it confirmed as destroyed was if our AA gunners had seen it go in, and to do that the fight had to be within a mile or two of the lines.

Debriefing

Debriefing was a noisy free-for-all. After a fight the patrol, or most of it, would struggle in in twos and threes with the streamers of message bags flying from the rear guns of those claiming Huns. Each lot as they came in would beat up the hangars, and the intensity of this would indicate how individual crews were feeling, and how the fight had gone. After taxiing in, the crews, still in fighting kit, would gather round Major Johnstone and Packham3. The crews who had not been on the show would gather round them, and the NCOs and Air Mechanics of the squadron would press in all round to hear as much as they could, and especially to what had happened to the crews of their machines. Meanwhile the inner group made their verbal reports, mostly at the same time, to Johnstone and Packham.

“I fired a short burst and he turned over and went right down out of control” might mean what the speaker hoped it did or it might mean that the Hun did a half roll and beat it for home. There was no way of telling, and many more enemy aircraft went ‘right down out of control’ than ever hit the ground, but one got to know who were the line-shooters who so often managed to ‘see him crash’, and who were the ones who tried to report only what they thought they had seen. It was usually the former who, at the end of a fight, were the furthest west and nearest home. Once, after a show I had been leading, I broke in on one of those who was shooting a line to the C.O. that I knew to be untrue and I called him a “bloody liar”. There was silence for a moment as he turned and elbowed his way out of the crowd, and then the gaggle went on as before.

Excerpt from The Memoirs of Thomas Cathcart Traill, ch.7 20 Squadron. Ypres/Bailleul. pp. 54-56

- Percy Griffith Jones ↩︎

- Major Johnstone: Commanding Officer ↩︎

- Captain A.T. Packham: Recording Officer (Adjutant) ↩︎